This spring I took Mother down to Advance for a Past Matrons meeting. After it was over, one of her friends insisted that we drive down to Bloomfield to see the new Missouri Veterans Cemetery and the Stoddard County Confederate Memorial, which I’ve already written about. She also said we should see the Stars and Stripes Museum / Library.

This spring I took Mother down to Advance for a Past Matrons meeting. After it was over, one of her friends insisted that we drive down to Bloomfield to see the new Missouri Veterans Cemetery and the Stoddard County Confederate Memorial, which I’ve already written about. She also said we should see the Stars and Stripes Museum / Library.

To be honest, I wasn’t all that crazy about going to the museum. It’s pretty nondescript looking from the outside. I figured I’d walk in, shoot a few pictures to be polite, then be back in the car in 15 minutes. I was hooked. We spent about an hour and a half in the place and didn’t begin to scratch the surface.

First off, I was vaguely familiar with Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper. I knew that cartoonist Bill Maudlin and bush-eyebrowed Andy Rooney worked for it. I knew that General Patton tried to get it banned and Ike overruled him.

First edition printed in Bloomfield

What I DIDN’T know was that the newspaper started right here in Bloomfield, Mo., when soldiers from the Illinois 8th, 11th, 18th and 29th regiments found the Bloomfield newspaper office empty and decided to publish a newspaper, The Stars and Stripes. It was the first and only newspaper published there, but it started a tradition that continued through both World Wars, Korea, Vietnam and our excursions into the Gulf today.

What I DIDN’T know was that the newspaper started right here in Bloomfield, Mo., when soldiers from the Illinois 8th, 11th, 18th and 29th regiments found the Bloomfield newspaper office empty and decided to publish a newspaper, The Stars and Stripes. It was the first and only newspaper published there, but it started a tradition that continued through both World Wars, Korea, Vietnam and our excursions into the Gulf today.

The Stars and Stripes Association, made up of former and present staffers, has a 30-minute video on its website detailing the life of the publication. I was glued to it.

Andy Rooney video

There’s a video at the museum of the late Andy Rooney telling about his stint with the newspaper and how Patton tried to shut it down.

There’s a video at the museum of the late Andy Rooney telling about his stint with the newspaper and how Patton tried to shut it down.

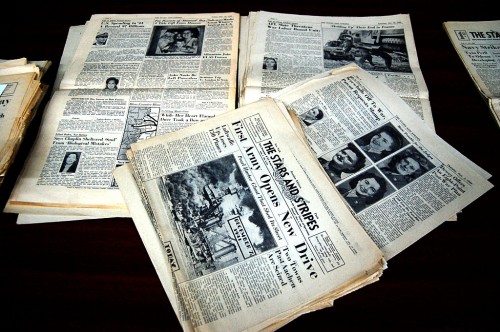

You can touch the newspapers

The thing that struck me more than the exhibits, which are really well done, was that copies of the newspaper were spread out on tables where you could touch them, read them and discover stories that brought history alive. A story on the front page of the Sept. 27, 1945, edition said, “Gen George S. Patton Jr. described his comparison of Nazi power politics with Republican-Democratic party battles at a press conference last week as ‘an unfortunate analogy.'”

The thing that struck me more than the exhibits, which are really well done, was that copies of the newspaper were spread out on tables where you could touch them, read them and discover stories that brought history alive. A story on the front page of the Sept. 27, 1945, edition said, “Gen George S. Patton Jr. described his comparison of Nazi power politics with Republican-Democratic party battles at a press conference last week as ‘an unfortunate analogy.'”

The more things change, the more they remain the same.

Helpful Librarian Sue Mayo

Librarian Sue Mayo made us feel welcome and pointed out things we would have missed. The site is billed as a “Museum / Library.” I have the feeling you could do some serious research here. I would have written about the museum earlier, but the Stars and Stripes website has been down and I wanted to be able to link to it.

Librarian Sue Mayo made us feel welcome and pointed out things we would have missed. The site is billed as a “Museum / Library.” I have the feeling you could do some serious research here. I would have written about the museum earlier, but the Stars and Stripes website has been down and I wanted to be able to link to it.

The museum and the Missouri Veterans Cemetery are side-by-side, so the same directions apply:

- From Highway 60 take Highway 25 north exit toward Bloomfield. Travel approximately 4 miles north and the cemetery and museum will be located on the west side of Highway 25.

- If arriving from the north on Highway 25, travel through Bloomfield and the cemetery and museum will be located at the southern edge of Bloomfield on the west side of the road.

Photo Galley of the Stars and Stripes Museum

Click on any photo to maker it larger, then click on the left or right side of the image to step through the gallery. We’ll have a story on Friday about servicemen from Perry County to commemorate Veterans Day.