By the time you read this, Cairo may or may not still be there. It all depends on how much higher the river gets and whether the Corps of Engineers has to blow the levee at Bird’s Point to reduce pressure on the city’s floodwall.

By the time you read this, Cairo may or may not still be there. It all depends on how much higher the river gets and whether the Corps of Engineers has to blow the levee at Bird’s Point to reduce pressure on the city’s floodwall.

I’m not going to get into the Sophie’s choice argument about whether farms in Missouri should be flooded to save a city in Illinois.

I am going to spend several days sharing photos that I hope will answer those folks who ask, “Why should we care about Cairo?”

Fort Defiance

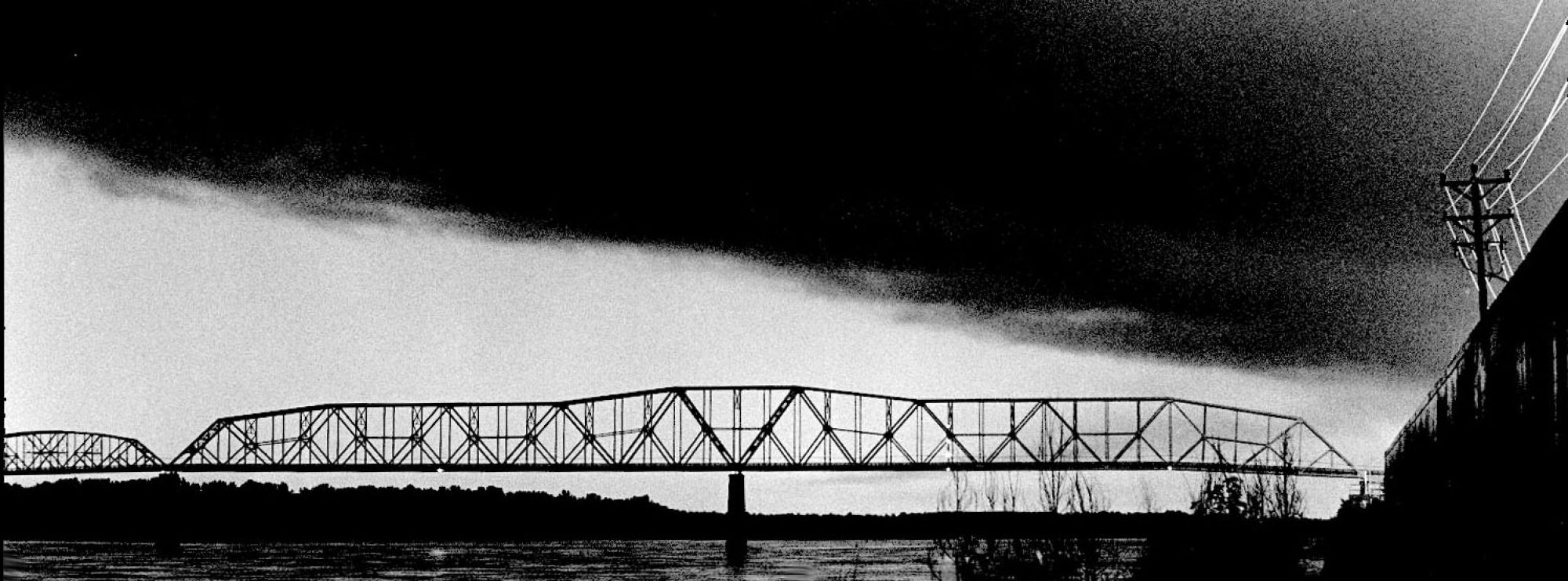

I was on my way back to Ohio Oct. 14, 1968, when I shot this photo at Fort Defiance, the southernmost point in Illinois, where the waters of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers meet It’s long been one of my favorite pictures.

Songwriter Stace England wrote an album of songs about Cairo. One is titled, The North Starts in Cairo, where he points out that black bus travelers coming from the South were segregated from whites by a curtain until they crossed the Ohio River into Cairo. Here’s a sample of The North Starts In Cairo. It’s worth buying the whole Greetings From Cairo, Illinois album.

It’s a great selection of songs, all historically accurate and done in a variety of ways.

Where the waters mingle

How safe is that flood gate?

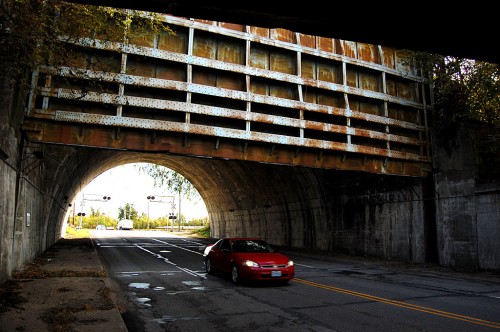

I’m sure that everyone who has driven under the massive flood gate at the north end of the city has wondered, just how safe is that thing, anyhow?

A plaque in the tunnel says “The Big Subway Gate” was built in 1914. It’s 60 feet wide, 24 feet high and five feet thick. Even though it weighs 80 tons, it has a counterweight that weighs almost as much, so it can be operated by two men, one at each end.

The other thing that Dad always impressed upon me was that Cairo was a notorious speed trap. Don’t go even one mile per hour over the limit, he warned on every trip through.

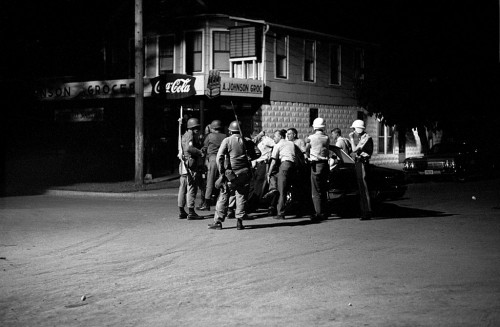

My first riot

I covered my first riot in Cairo. Actually, by the time I got there, the National Guard had been called out and things had pretty much settled down. Still, I learned some lessons that served me well during the turbulent 60s and 70s and 80s.

I covered my first riot in Cairo. Actually, by the time I got there, the National Guard had been called out and things had pretty much settled down. Still, I learned some lessons that served me well during the turbulent 60s and 70s and 80s.

I’ll have photos from July 1967 and will touch on the turmoil that sent the city’s population into a freefall.

Elegant mansions

Cairo is noted for its historic buildings. The Magnolia Manor is one of the most famous. Within a block of it, I saw one that could be fixed up equally as nicely for an unbelievably low price.

I have to admit that I haven’t spent much time on the pretty side of town. Years ago, when I was first getting into this racket, someone asked, “Do you want to shoot for National Geographic?”

I responded, “I don’t think that’ll work out. National Geographic photographers stand on trash cans to shoot pretty pictures of roses. I trample roses to shoot photos of trash cans.”

Collapsing buildings

It’s equally noted for its decaying buildings. I took this picture Oct. 28, 2008.

It’s equally noted for its decaying buildings. I took this picture Oct. 28, 2008.

Whole block knocked down

When I came back in April of 2010, the whole block had been knocked down.

When I came back in April of 2010, the whole block had been knocked down.

“Why?” the sign asks

“Why?” reads the sign on what I think had been a bar. I’m assuming the 1933-2005 refers to the years of operation.

“Why?” reads the sign on what I think had been a bar. I’m assuming the 1933-2005 refers to the years of operation.

The bigger question is “Why didn’t a city located at the confluence of two of the nation’s largest rivers ever meet its potential?”

I ask your indulgence while I step outside Cape County for a few days to share with you some of the hundreds of photos I’ve taken in Cairo over the last nearly 50 years.

I hope it’ll still be there on my return. The bridge leading to Wickliffe was closed, so I couldn’t go that way on my way back to Florida this trip.