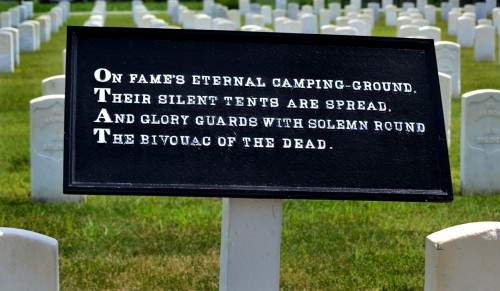

[Editor’s Note: The following is taken from April 5, 1894, Obituaries and Death Notices of The Cairo Citizen. I have preserved the spelling and grammar of the original piece, including the curious practice of inserting subheads in the middle of sentences. I usually place long quotes in italics, but I’m reserving that font for my comments this time. The photos were taken in the Mound City National Cemetery. Click on the images to make them larger.]

[Editor’s Note: The following is taken from April 5, 1894, Obituaries and Death Notices of The Cairo Citizen. I have preserved the spelling and grammar of the original piece, including the curious practice of inserting subheads in the middle of sentences. I usually place long quotes in italics, but I’m reserving that font for my comments this time. The photos were taken in the Mound City National Cemetery. Click on the images to make them larger.]

A WEIRD TALE.

After Thirty Years a Grave Gives up Its Secret.

After Thirty Years a Grave Gives up Its Secret.

“Curly Kate” Story at Last Explained

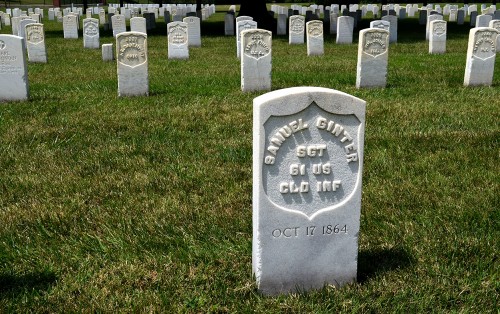

It has been truly said that “truth is stranger than fiction.” The recent discovery that Sam Ginter of the 61st United States colored infantry was buried as “Unknown” at the beautiful national cemetery at Mound City, is but another exemplification of that old adage.

The fact that the identity of an unknown soldier has been discovered after a period of thirty years’ burial, is in itself a remarkable occurrence, but when that soldier’s grave has been surrounded by speculations, hatreds, and slanders, base and cruel, the story of its occupant’s life and death is doubly interesting. The facts and circumstances surrounding the grave of Sam Ginter have already made a sensational chapter in the history of Cairo, but the tale itself should be again told, in order that the reader may see the force and meaning of subsequent events.

The City of the Dead

In the early spring of 1889, the present fairgrounds were still sacred as the city of the dead. But in the summer of that same year the old graveyard, with its solemn and sacred stillness, was turned into a place of frolic and merriment.

In the early spring of 1889, the present fairgrounds were still sacred as the city of the dead. But in the summer of that same year the old graveyard, with its solemn and sacred stillness, was turned into a place of frolic and merriment.

On the afternoon of Tuesday, June 25th, 1889, while exhuming the bones of the silent inhabitants of the old cemetery, the workmen came across a fine metallic coffin, of the character used during the late war. It was of cast iron ________ in the style of a bath ___, the top being bolted to the lower part, and the seam made tight by lead packing.

There was a glass top to the casket, and through this, by the aid of reflection, it could be seen that the body was that of a Union soldier. It looked as though there was a double row of buttons upon the coat, and the body was immediately called that of THE UNKNOWN MAJOR.

Body was taken to National Cemetery

The casket was taken in charge by Warren Stewart Post No. 533, G. A.R. and a committee consisting of Rev. J. W. Phillips, Judge J. R. Robinson and Capt. N. B. Thistlewood, were appointed to re-inter the body at the national cemetery at Mound City. On the afternoon of Thursday, June 27th, 1889, the body of this unknown soldier was again laid to rest.

The casket was taken in charge by Warren Stewart Post No. 533, G. A.R. and a committee consisting of Rev. J. W. Phillips, Judge J. R. Robinson and Capt. N. B. Thistlewood, were appointed to re-inter the body at the national cemetery at Mound City. On the afternoon of Thursday, June 27th, 1889, the body of this unknown soldier was again laid to rest.

The description as made out through the beclouded glass, was thought to be that of a “young man, about five feet nine inches in height, fair, rather light complexioned, light hair, eye tooth on the left missing, dressed in the uniform of a major of the infantry, gold buttons on his shoulder straps, while the gold leaf at each end was clear and distinct, as well as the blue ground that indicated the branch of the service.”

At this point the story might have ended, but the editor of a local daily paper, who is now connected with the Chicago Inter-Ocean, decided otherwise. On the morning of Sunday, July 14, 1889, in a four-column article he dilated on an alleged mystery under the headlines

“IS SHE THE UNKNOWN MAJOR?”

“Can Curly Kate be buried by mistake in our national cemetery?”

“Can Curly Kate be buried by mistake in our national cemetery?”

In this article the editor claimed to have received a letter from Cincinnati, signed “Nellie,” in which the writer said that the “dead major” was none other than “Curly Kate” a noted courtesan, who flourished in Cairo during the war. In this alleged letter “Nellie” said that she and Kate had been companions in Cairo, but owing to their forcible ejectment from the city by the commanding officer, in the interests of morality, they had returned in soldier’s uniform and were compelled thereafter to go about in that garb.

One evening Kate, in the uniform of a major, went out boating with a gentleman who is now one of our leading businessmen, but never returned; the “writer” alleging that Kate had been murdered by the male companion who confiscated $5,000 which she had on her person. This sensational article created intense excitement and

NEARLY LED TO A TRAGEDY;

the gentleman so basely slandered naturally being very angry. The paper, which published this libelous and sensational article, stood alone, the balance of the press fighting it at every point.

the gentleman so basely slandered naturally being very angry. The paper, which published this libelous and sensational article, stood alone, the balance of the press fighting it at every point.

Matters finally became so complicated that an order was obtained from the authorities at Washington to re-exhume the body and examine it. Late in the afternoon of August 4, 1889, a deputation of citizens went up from Cairo to the national cemetery and the body was again unearthed.

The excitement was intense and men crowded around the grave to get a glimpse of the mysterious unknown. A committee of physicians consisting of Dr. Casey of Mound City, and Drs. Stevenson, Sullivan, McNemer, Rendleman, and Malone, of Cairo, examined the wasted and sunken features and then made further and more critical examination. It took but a moment for them to discover that

THE BODY WAS THAT OF A MAN.

The final and minute examination of the body gave birth to the following description: Five feet ten inches high, seventeen or eighteen years of age; well built and rather stocky, good symmetrical features which were small and well shapen, intelligent face, high forehead. Eyetooth missing on left side. Flaxen, auburn hair, with a tendency to ringlets. Covered with a common gray army blanket from the waist down. Feet tied together with a hempen string. No papers or any mark of identification on the body. Uniform of a common soldier.

The final and minute examination of the body gave birth to the following description: Five feet ten inches high, seventeen or eighteen years of age; well built and rather stocky, good symmetrical features which were small and well shapen, intelligent face, high forehead. Eyetooth missing on left side. Flaxen, auburn hair, with a tendency to ringlets. Covered with a common gray army blanket from the waist down. Feet tied together with a hempen string. No papers or any mark of identification on the body. Uniform of a common soldier.

The body was not that of “Curly Kate.” But whose was it? What common soldier could have been buried at such expense, and then forgotten? These questions puzzled everyone acquainted with the story, and have even to this day.

HON. W. N. BUTLER SOLVES THE MYSTERY.

In the same issue of the Chicago Record of March 9th, this year, there appeared an article from Mason, Ill. State’s Attorney Butler, who is a subscriber for that paper, read the account and became very much interested. The story is substantially as follows: Dr. W. B. Dennis, of Effingham, Ill. was hospital steward of the 61st United States colored infantry at the time the following events took place. Under command of Col. Sturgis the regiment was ordered to leave Memphis by transfer boat for the upper Tennessee River.

In the same issue of the Chicago Record of March 9th, this year, there appeared an article from Mason, Ill. State’s Attorney Butler, who is a subscriber for that paper, read the account and became very much interested. The story is substantially as follows: Dr. W. B. Dennis, of Effingham, Ill. was hospital steward of the 61st United States colored infantry at the time the following events took place. Under command of Col. Sturgis the regiment was ordered to leave Memphis by transfer boat for the upper Tennessee River.

Near Paducah the boat was signaled by two men on shore who were supposed to be Union couriers. They were taken on board and delivered dispatches to the commanding officer, presumably from the federal general. The dispatches ordered the regiment to proceed to a place called Eastport. There to disembark and march inland about four miles where they were to destroy a bridge, and thus cut off the retreat of the Rebel General Forrest.

Those two men were in reality, Rebel spies, and the object was to lead the Federals into an ambush. The place of destination, Eastport, was a hamlet of about fifty people, in Tishomingo County, Miss. This county is in the northeast corner of the state, the Tennessee River cutting off the northeast corner of the county and forming the border of the state.

SLAUGHTERED IN AMBUSH

On October 10th, 1864, the regiment reached Eastport and about two-thirds were landed. They had scarcely reached the shore before they were swept down by a withering fire from two sides. Sixteen were instantly killed and twenty wounded. In great disorder they rushed for the boat, which had broken from its moorings and was floating down stream.

On October 10th, 1864, the regiment reached Eastport and about two-thirds were landed. They had scarcely reached the shore before they were swept down by a withering fire from two sides. Sixteen were instantly killed and twenty wounded. In great disorder they rushed for the boat, which had broken from its moorings and was floating down stream.  Less than half of those who landed reached the boat. Dr. Dennis and a comrade of the name of Sam Ginter were endeavoring to pull a cannon up the gangway, when a shell burst and both fell apparently dead. Ginter receiving many wounds. They were both carried into the stateroom.

Less than half of those who landed reached the boat. Dr. Dennis and a comrade of the name of Sam Ginter were endeavoring to pull a cannon up the gangway, when a shell burst and both fell apparently dead. Ginter receiving many wounds. They were both carried into the stateroom.

A deck hand prowling about for plunder discovered that Dr. Dennis was alive and so reported to his superior officers. Dr. Dennis had not received a scratch, but the terrible concussion had so affected his brain that he could recall none of the circumstances of the battle. The officers of the regiment made up a purse of $360 for the purpose of embalming Ginter, and sending his body to his widowed mother, who lived near Bloomington, Ill. Dr. Dennis was granted a furlough to visit his relatives in Ohio and was also selected to accompany the remains of Ginter to Bloomington.

It might here be stated that the regiment was composed of colored soldiers, and although Ginter was a private, being a white man and detailed to special duty, he had only associated with the officers who were, of course, white. The officers had conceived a great liking for Ginter, and when he was killed, made up a purse for a decent burial, in order that they might testify to their appreciation of is worth.

Dr. Dennis

REMEMBERS REACHING THE CAIRO WHARF

and standing for a moment on the levee to wave a farewell to his companions. He then turned to go up the hill to have the body embalmed. After this he remembers nothing; his mind is a perfect blank as to the following two weeks. He has no recollection of what he did with the body. He even lost his own identity for that period.

and standing for a moment on the levee to wave a farewell to his companions. He then turned to go up the hill to have the body embalmed. After this he remembers nothing; his mind is a perfect blank as to the following two weeks. He has no recollection of what he did with the body. He even lost his own identity for that period.

The next thing he remembers, he was walking up the streets of Memphis, clad in new clothes. One of the negro soldiers recognized him and offered to carry his valise to headquarters. When questioned about his trip and the disposition of Ginter’s body, he could remember nothing—knew nothing of what they were talking.

He was then questioned about the $360, which had been left in his care, for the purpose of having Ginter’s body embalmed. He had no recollection of this incident, but upon searching his clothing, the money was found intact, in his inside vest pocket. Gradually the incidents of the battle and his trip to Cairo became more firmly impressed upon his mind, but recollection as to the subsequent two weeks was then a blank and remains so to this day.

GINTER WAS THE UNKNOWN SOLDER

Upon reading this article, Mr. Butler became convinced that alleged to have been “Curly Kate.” As he was personally acquainted with Dr. J. N. Matthews, the Mason correspondent of the Record, Mr. Butler wrote to that gentleman a full description of the body found in the old graveyard, and related the “Curly Kate” episode.

Upon reading this article, Mr. Butler became convinced that alleged to have been “Curly Kate.” As he was personally acquainted with Dr. J. N. Matthews, the Mason correspondent of the Record, Mr. Butler wrote to that gentleman a full description of the body found in the old graveyard, and related the “Curly Kate” episode.

Dr. Matthews immediately left for Effingham and laid the letter from Mr. Butler before Dr. Dennis. Dr. Dennis was dumbfounded. After thirty years of silence he had discovered where Ginter’s body had been placed, and furthermore said that Mr. Butler’s description of the unknown soldier

TALLIED EXACTLY WITH THAT OF GINTER.

In his mind there is not the slightest doubt but that the body of Ginter, surrounded as it has been by sensations and occurrences stranger even that the most sensational romance, has at last been discovered. Dr. Dennis’ theory of this strange sequel to his remarkable experience, is as follows:

In his mind there is not the slightest doubt but that the body of Ginter, surrounded as it has been by sensations and occurrences stranger even that the most sensational romance, has at last been discovered. Dr. Dennis’ theory of this strange sequel to his remarkable experience, is as follows:

“Having reached Cairo and engaged the undertaker, I purchased the casket while still able to transact business, paying a certain guaranty from my own pocket book, and arranging to settle the rest of the cost when I called for the remains, after the embalming process. And then my mental aberration growing worse, I wandered off and never returned, leaving the body to be cared for by strangers. Being an officer, I had money of my own, and this probably accounts for my not using the money contributed by my comrades.

“I am considerably exercised over the disclosures, but my own whereabouts and condition at that time, beyond theory, are as much of a mystery as ever. The description given Mr. Butler of the corpse disinterred at Cairo, tallies in every particular with that of my comrade, Ginter, and I have no hesitancy in pronouncing this to be the body of my long lost comrade.”

The story is ended

The story is ended. It has been told without a single addition or embellishment, but we believe that a romancer never wove a fancy, more exciting or more unreal than this tale of the war. After thirty years of agony, Dr. Dennis can write to that widowed old mother and tell her that the body of her son lies sleeping in a soldier’s grave beneath the peaceful shades of the beautiful trees at the soldiers’ cemetery. The hatred and malice of men tried even to malign him as he slept there, but they failed, and though his ashes were rudely disturbed, the evil that was intended has ended in a blessing.

The story is ended. It has been told without a single addition or embellishment, but we believe that a romancer never wove a fancy, more exciting or more unreal than this tale of the war. After thirty years of agony, Dr. Dennis can write to that widowed old mother and tell her that the body of her son lies sleeping in a soldier’s grave beneath the peaceful shades of the beautiful trees at the soldiers’ cemetery. The hatred and malice of men tried even to malign him as he slept there, but they failed, and though his ashes were rudely disturbed, the evil that was intended has ended in a blessing.

(A marker at Grave 3396 Section E in Mound City National Cemetery reads: Sgt. Samuel Ginter U.S. Army Oct. 17, 1864.—Darrel Dexter)

[Editor’s note: Thanks to Darrel Dexter for transcribing the Obituaries and Death Notices of The Cairo Citizen for the period of January 4, 1894 to December 27, 1894. They are fascinating reading. I referred to some in my post about the Mt. Moriah Missionary Baptist Church. Mound City’s cemetery isn’t the only National Cemetery with a mystery grave: check out the story of Dennis O’Leary in the Santa Fe National Cemetery.]