My eye kept being drawn to something colorful under the huge flag at North County Park.

My eye kept being drawn to something colorful under the huge flag at North County Park.

The weather geeks had been promising stormy weather for Saturday, which included 70 mph winds and golfball-sized hail. When the radar started looking nasty, I decided to go mobile to get the car under cover if the hail really did arrive. That gave me an excuse to cruise by the park, but still stay close to my hidey-hole.

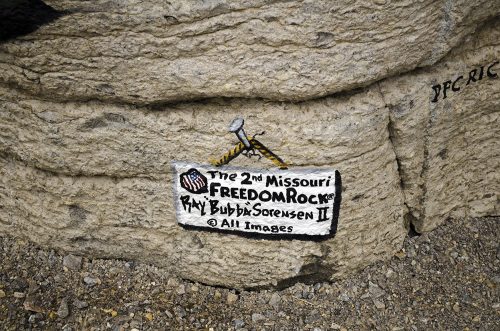

Work done by ‘Bubba’ Sorensen II

The Freedom Rock artwork was done by Ray “Bubba” Sorensen II on a 32-ton limestone boulder that came from the Buzzi Unicem quarry. He painted his first rock in 1999 in his home state of Iowa. This will be his 59th creation, only the second in Missouri. All but three of the 59 are in Iowa. You can get the whole story in a Southeast Missourian piece by Mark Bliss.

The Freedom Rock artwork was done by Ray “Bubba” Sorensen II on a 32-ton limestone boulder that came from the Buzzi Unicem quarry. He painted his first rock in 1999 in his home state of Iowa. This will be his 59th creation, only the second in Missouri. All but three of the 59 are in Iowa. You can get the whole story in a Southeast Missourian piece by Mark Bliss.

Click on the photos to make them larger.

Back depicts avenue of flags

The back of the stone has a rendition of the veterans’ flags donated by their families and displayed on holidays.

The back of the stone has a rendition of the veterans’ flags donated by their families and displayed on holidays.

Battleship USS Missouri

The Battleship USS Missouri appears on one end of the stone. It was on the deck of that ship that the Japanese signed the surrender that ended World War II.

The Battleship USS Missouri appears on one end of the stone. It was on the deck of that ship that the Japanese signed the surrender that ended World War II.

Cox and Willard

Prominent Missouri military men are recognized. Maj. Gen. John V. Cox was born and raised in Bevier, Mo., in Macon County. He joined the Marines in 1952, and served two tours in Vietnam, where he flew 200 combat missions, and logged 4,000 accident-free flying hours.

Prominent Missouri military men are recognized. Maj. Gen. John V. Cox was born and raised in Bevier, Mo., in Macon County. He joined the Marines in 1952, and served two tours in Vietnam, where he flew 200 combat missions, and logged 4,000 accident-free flying hours.

Vice Adm. Arthur L. Willard’s career almost ended before it started when he and 15 other cadets were expelled from the U.S. Naval Academy over a hazing scandal in 1888. Missouri Congressman William M. Hatch interceded with President Grover Cleveland to get him reinstated. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, he led a shore party under fire to raise the American flag over a Spanish blockhouse in Cuba. The Missouri legislature presented him with a jeweled officer’s sword for his efforts. (The New York Herald gave him a $100 prize for being the first U.S. serviceman to raise the American flag on Cuban soil.) He received the Navy Cross for being able to solve logistical problems during World War I.

Gen. McKee was a Cape boy

Gen. Seth J. McKee, graduated from Cape Central High School in 1934, and attended Southeast Missouri State College from 1934 to 1937. At the time of his death at 100 in 2016, he was the oldest survivor of the D-Day invasion of France in World War II. He ended his career as commander of the North American Air Defense Command. It is said one of his retirement gifts was a replica of the red phone he would have used to notify the president that the country had come under nuclear attack. Mark Bliss wrote an obituary that contains more details.

Gen. Seth J. McKee, graduated from Cape Central High School in 1934, and attended Southeast Missouri State College from 1934 to 1937. At the time of his death at 100 in 2016, he was the oldest survivor of the D-Day invasion of France in World War II. He ended his career as commander of the North American Air Defense Command. It is said one of his retirement gifts was a replica of the red phone he would have used to notify the president that the country had come under nuclear attack. Mark Bliss wrote an obituary that contains more details.

Stephen W. Thompson was born in West Plains, Mo., and joined the army when the U.S. entered World War I in 1917. On the way to Virginia for training in the Coast Artillery Corps, he saw his first airplane. After his first flight, he switched to the Air Service. Even though his squadron had not yet begun combat operations, Thompson and a buddy hopped aboard French aircraft to serve as gunner-bombardiers. On that flight, he managed to shoot down an attacking fighter, the first aerial victory by any member of the U.S. military. He was awarded the Croix de guerre by the French government.

Gen. Roscoe Robinson Jr.

Gen. Roscoe Robinson, Jr., born in St. Louis, was the first African-American to become a four-star general in the U.S. Army. He served as a platoon leader and rifle company commander in Korea in 1952, where he was awarded the Bronze Star. In 1967, he served as a battalion commander in Vietnam. For that service, he was awarded the Legion of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, 11 Air Medals, and two Silver Stars.

Gen. Roscoe Robinson, Jr., born in St. Louis, was the first African-American to become a four-star general in the U.S. Army. He served as a platoon leader and rifle company commander in Korea in 1952, where he was awarded the Bronze Star. In 1967, he served as a battalion commander in Vietnam. For that service, he was awarded the Legion of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, 11 Air Medals, and two Silver Stars.

Cape’s Medal of Honor recipient

PFC Richard G. Wilson was born in Marion, Ill., but moved to Cape Girardeau in 1939. He attended May Greene School and Central High School, where he played guard on the football team.

PFC Richard G. Wilson was born in Marion, Ill., but moved to Cape Girardeau in 1939. He attended May Greene School and Central High School, where he played guard on the football team.

Wilson served in Korea as a private first class with the 187th Airborne Infantry Regiment. On October 21, 1950, he was attached to Company I when the unit was ambushed while conducting a reconnaissance in force mission near Opa-ri. Wilson exposed himself to hostile fire in order to treat the many casualties and, when the company began to withdraw, he helped evacuate the wounded. After the withdrawal was complete, he learned that a soldier left behind and believed dead had been spotted trying to crawl to safety. Unarmed and against the advice of his comrades, Wilson returned to the ambush site in an attempt to rescue the wounded man. His body was found two days later, lying next to that of the man he had tried to save. For these actions, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor on August 2, 1951.