I made semi-annual pilgrimages to this building displaying a boot for at least 20 years.

I made semi-annual pilgrimages to this building displaying a boot for at least 20 years.

The Missourian announced on Jan. 27, 1985, that Bob’s Shoe Service at 515 Broadway was expanding. Owner Bob Fuller bought the building on the right from C.W. Bauerle, doubling his space from 1,500 square feet to 3,000.

The story said that Fuller had “been in the shoe repair business for 32 years, and in addition to this engaged for a time in making saddles, and at the present produces leather belts and other items. Fuller is assisted in his business by his sons, Wade and Scott.”

I’m not sure exactly when I bought my first pair of Red Wing boots, but it was sometime between The Athens Messenger and The Gastonia Gazette in the late 60s – early 70s.

Shoes through the ages

[Note the reflection in the bottom left of the photo. Click on it to make it larger. The Walther’s sign hadn’t been changed to Discovery Playhouse yet. These pictures were taken Oct. 24, 2009.]

[Note the reflection in the bottom left of the photo. Click on it to make it larger. The Walther’s sign hadn’t been changed to Discovery Playhouse yet. These pictures were taken Oct. 24, 2009.]

I was no stranger to manly, blue collar shoes. Even back in grade school I wore a modified high lace-up combat-style boot. When I worked for Dad one summer, I had some low-cut work shoes that were sturdy and serviceable.

I think I wore loafers in high school. Not penny loafers, I’m positive. No tassels, either.

When I went away to college, I recall going through a Hush Puppy suede shoe stage. At some point, I bought some fur-lined slip-on boots in Ohio that were nice and warm when it got cold and nasty. I wore them until they became, shall we say, odoriferous, and I passed them on to Brother David, who wore them many more years. He lived in Oklahoma, where standards were lower.

Red Wing boots: perfect photographer shoes

Something lured me into Bob’s, where I discovered the Red Wing work boot, which I thought was the perfect footwear for a newspaper photographer.

Something lured me into Bob’s, where I discovered the Red Wing work boot, which I thought was the perfect footwear for a newspaper photographer.

- They were quick to slip into.

- If you polished them, they’d take a shine like an expensive dress shoe.

- If you put mink oil on them, they’d get soft and repel water.

- They were high enough that you didn’t have to worry about wading through water, sand or mud. (And, it didn’t matter if your socks matched. You couldn’t see them.)

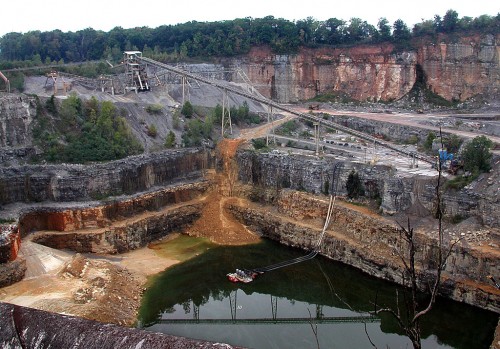

- You could climb rock cliffs, walk through construction sites without worrying about stepping on nails and be reasonably certain that you were safe from snakebite as long as you were around lazy snakes.

No BS uniform

Every once in awhile I’d want to go onto a construction site to shoot pictures, but some foreman would say, “Well, I’D give you permission, but you have to have a hard hat and the right kind of shoes. Safety regulations, you know. Sorry.”

Every once in awhile I’d want to go onto a construction site to shoot pictures, but some foreman would say, “Well, I’D give you permission, but you have to have a hard hat and the right kind of shoes. Safety regulations, you know. Sorry.”

I’d walk back to my car and dig out my safety-approved white hard hat. On the front of it was a drawing of a bull squatting down making a deposit, surrounded by the international symbol for “No.” I’d return to the foreman, don my “No BS” hard hat, hike up my pants leg to display my Red Wing boots and say, “OK now?”

Rarely did the foreman come up with another hoop for me to jump through.

Boots cost more than a suit

The only drawback was that the boots cost $75 in the days when you could buy a SUIT for $25. OK, let me amend that. I could buy a suit for $25.

The only drawback was that the boots cost $75 in the days when you could buy a SUIT for $25. OK, let me amend that. I could buy a suit for $25.

Despite the high cost – more than half a week’s pay – I usually had at least three pair of the boots in wearing sequence.

- A new pair for when I needed to be presentable – that set was polished.

- The ones I wore for work – mink oiled and waterproofed.

- A beat-up pair kept in the trunk for truly grody situations.

It just dawned on me that I haven’t seen a pair of Red Wing boots in the closet since Son Matt got big enough to wear my shoes.