Sometime back in the 70s, I heard that the Marquette cement plant was going to blow the caves that had been made to quarry limestone in the days before heavy equipment made removing overburden easy. (Click on any photo to make it larger.)

Sometime back in the 70s, I heard that the Marquette cement plant was going to blow the caves that had been made to quarry limestone in the days before heavy equipment made removing overburden easy. (Click on any photo to make it larger.)

It might have been The Missourian’s story with a whole page of Fred Lynch photos on Page 6 that tipped me off. Here’s the link to the story about the caves. You’ll have to page back to see his pictures.

Pitched story to architectural magazine

I pitched the story idea to an architectural magazine. They wouldn’t give me an assignment, but they said they’d look at whatever I shot. I don’t recall if they eventually turned the story down or if I never got around to submitting it to them. I think it was the latter.

I pitched the story idea to an architectural magazine. They wouldn’t give me an assignment, but they said they’d look at whatever I shot. I don’t recall if they eventually turned the story down or if I never got around to submitting it to them. I think it was the latter.

So, the Kodachrome slides spent 30-plus years in storage, where the color shifted slightly.

Edward Hely founded company in 1904

The Missourian’s story said that Edward Hely started the stone company in 1904; it bore his name until 1931, when it became the Federal Materials Co. The quarry was known as the Blue Hole because of the color of the water when it filled up.

The Missourian’s story said that Edward Hely started the stone company in 1904; it bore his name until 1931, when it became the Federal Materials Co. The quarry was known as the Blue Hole because of the color of the water when it filled up.

Marquette Cement bought the property in 1976.

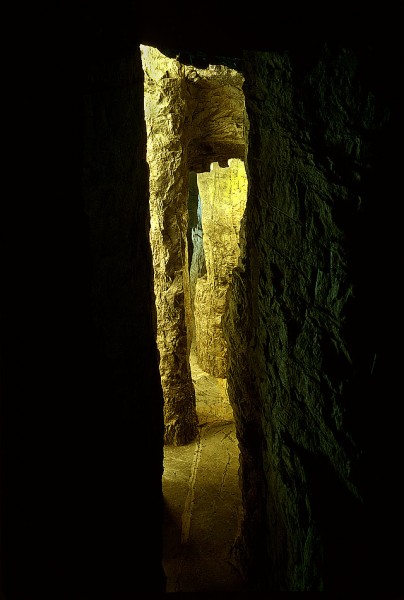

By the time Marquette Cement bought the property in 1976, the two quarries were separated by just about 100 feet, most of which was taken up by a network of caves. Federal Materials found it easier to dig horizontally to extract the limestone than to remove 35 to 50 feet of overburden – earth and lower grade stone – to get to the rock.

By the time Marquette Cement bought the property in 1976, the two quarries were separated by just about 100 feet, most of which was taken up by a network of caves. Federal Materials found it easier to dig horizontally to extract the limestone than to remove 35 to 50 feet of overburden – earth and lower grade stone – to get to the rock.

When the tunneling stopped, the quarry was about 375 feet deep. The pillars averaged 150 feet in height and were 35 to 45 feet in diameter.

Caves collapsed in 1981

In its May 17, 1981 edition, The Missourian pulled out all the stops to cover the collapse of the caves. Fred captured the action and reporter John Ramey wrote a first-person account of seeing a million tons of rock collapse on itself. The story said that crews spent two months drilling 850 blast holes and loading them with 600,000 pounds of dynamite. Some of the deepest 200-foot holes contained as much as 1,400 pounds of dynamite.

In its May 17, 1981 edition, The Missourian pulled out all the stops to cover the collapse of the caves. Fred captured the action and reporter John Ramey wrote a first-person account of seeing a million tons of rock collapse on itself. The story said that crews spent two months drilling 850 blast holes and loading them with 600,000 pounds of dynamite. Some of the deepest 200-foot holes contained as much as 1,400 pounds of dynamite.

You could walk a long way

Present-day Buzzi Unicem plant manager Steve Leus was part of the team that handled the blast. When he gave me a tour of the plant and the quarry last fall, he said, “I was in the caves myself. It was massive. You could walk a long way before you came to the end of that cave.”

Present-day Buzzi Unicem plant manager Steve Leus was part of the team that handled the blast. When he gave me a tour of the plant and the quarry last fall, he said, “I was in the caves myself. It was massive. You could walk a long way before you came to the end of that cave.”

Columns were massive

“The columns were massive,” he continued. “They had to be to hold up that roof.”

“The columns were massive,” he continued. “They had to be to hold up that roof.”

They way they mined in those days, he explained, was “they drilled into the side of the limestone, then they blasted, then they mucked it out. Basically what they ended up doing was tunneling.”

You wouldn’t make that mistake twice

“They had a feel for what size column to leave to support the roof, and, if they didn’t, they didn’t make that mistake twice,” Leus said.

“They had a feel for what size column to leave to support the roof, and, if they didn’t, they didn’t make that mistake twice,” Leus said.

Some of the tunnels are under Sprigg

Leus pointed out some of the tunnels that extend under Sprigg Street. “We don’t know how far back they go,” he said. Present-day safety regulations make it complicated to enter what is considered a mine, so no one in recent history has explored the caves. (I’ll have pictures of those in the future.)

Leus pointed out some of the tunnels that extend under Sprigg Street. “We don’t know how far back they go,” he said. Present-day safety regulations make it complicated to enter what is considered a mine, so no one in recent history has explored the caves. (I’ll have pictures of those in the future.)

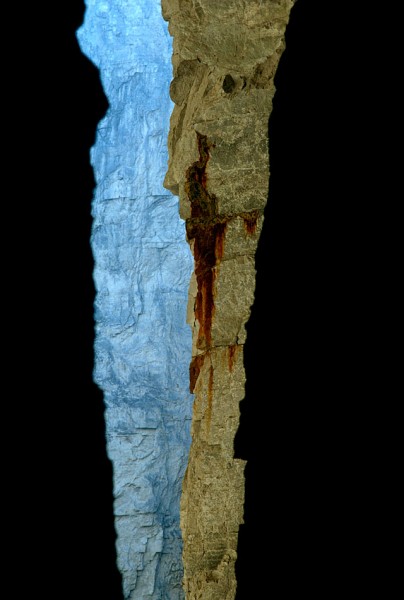

Seep water poured down sidewalls

Ground water would find its way into seams and leak down the walls of the quarry. Pumps would send it on its way through underground pipes until it made it back to the Mississippi River.

Ground water would find its way into seams and leak down the walls of the quarry. Pumps would send it on its way through underground pipes until it made it back to the Mississippi River.

Quarry was about 375 feet deep

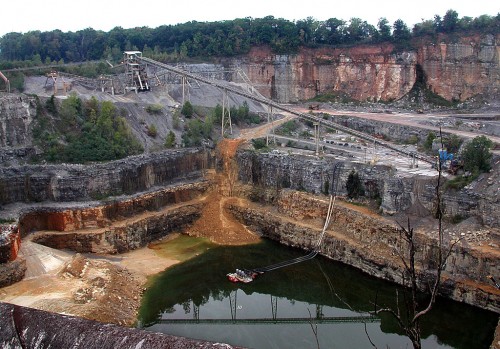

When Marquette Cement acquired the Federal Materials quarry, the deepest part was about 375 feet deep. Access to to the bottom was over rough, steep and curving haul roads.

When Marquette Cement acquired the Federal Materials quarry, the deepest part was about 375 feet deep. Access to to the bottom was over rough, steep and curving haul roads.

Shafts of light and darkness

You were constantly moving into areas of shade and darkness when you drove along the haul road and through the caves.

You were constantly moving into areas of shade and darkness when you drove along the haul road and through the caves.

Enough stone for another 10-15 years

Leus said there is enough stone in the quarry to last for another 10-15 years. They’re expanding to the north and west now since they’ve gone just about as deep as practical at this point.

Leus said there is enough stone in the quarry to last for another 10-15 years. They’re expanding to the north and west now since they’ve gone just about as deep as practical at this point.

A 1981 story estimated the reserves would last about 30 years, so either production has slowed or more rock is being extracted than predicted. The cement plant owns property near Scott City that could be mined in the future.

A place of beauty

There was something to shoot in every direction. This made me think of the grand canyon.

There was something to shoot in every direction. This made me think of the grand canyon.

A shame to lose them

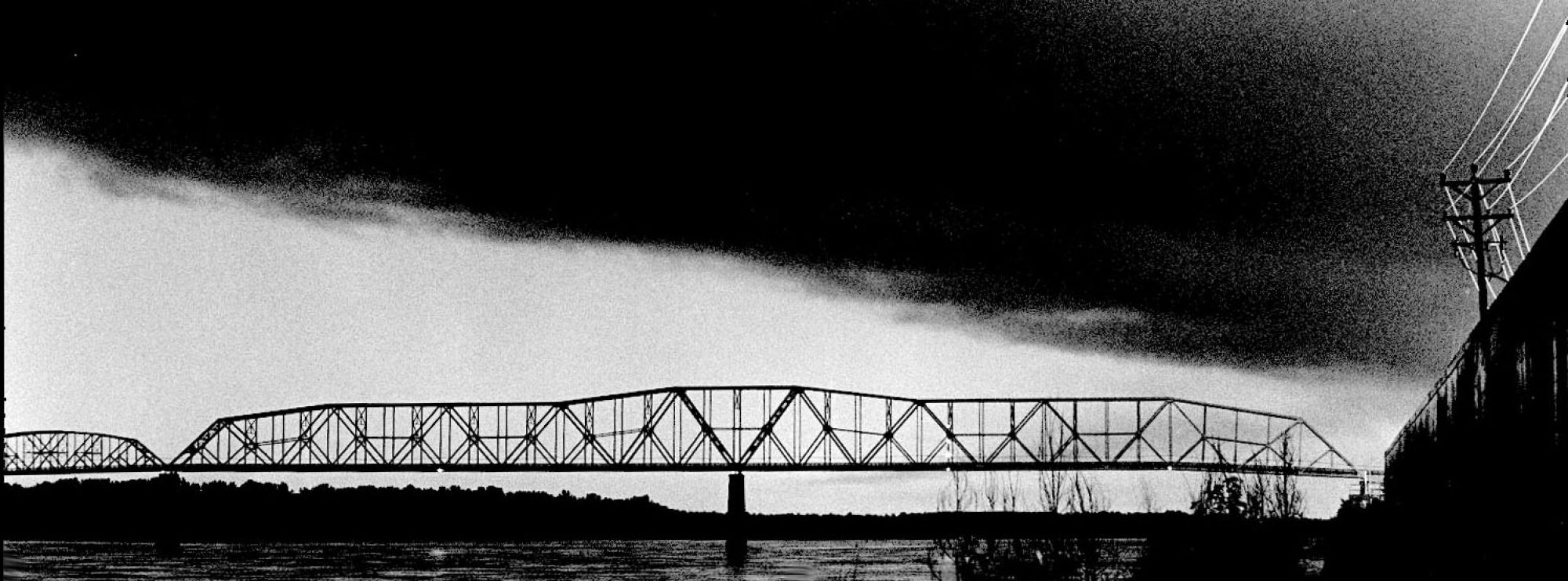

It was a shame to lose these beautiful features, but safety regulations would bar anyone from seeing them today, so it may be better that the stone was turned into the Bill Emerson Memorial Bridge and roads and buildings in the region.

It was a shame to lose these beautiful features, but safety regulations would bar anyone from seeing them today, so it may be better that the stone was turned into the Bill Emerson Memorial Bridge and roads and buildings in the region.

More photos to come

I’ll have more photos of the quarry and the cement plant taken last fall. Some of the photos from the 9th floor of the plant show spectacular views all the way to Academic Hall. The day was so clear that Crowley’s Ridge was visible in the distance.

I’ll have more photos of the quarry and the cement plant taken last fall. Some of the photos from the 9th floor of the plant show spectacular views all the way to Academic Hall. The day was so clear that Crowley’s Ridge was visible in the distance.