Way back in the spring, I received this rather long piece on Toilet Paper Wars in Cape. I held on to it, knowing that I would eventually find some photos to illustrate it. Reversing my normal style, I’ll put my comments in italic type so you can tell his words from mine. The writer is someone who contributes regularly, but under aliases. (I’d rather have real names, but this character has some viewpoints that are worth reading, even if I can’t identify him/her.) I also can’t tell you who the kids are in the photo, but I’m sure one of you will know them.

Way back in the spring, I received this rather long piece on Toilet Paper Wars in Cape. I held on to it, knowing that I would eventually find some photos to illustrate it. Reversing my normal style, I’ll put my comments in italic type so you can tell his words from mine. The writer is someone who contributes regularly, but under aliases. (I’d rather have real names, but this character has some viewpoints that are worth reading, even if I can’t identify him/her.) I also can’t tell you who the kids are in the photo, but I’m sure one of you will know them.

The Bun Wad War

By Anon

Beginning the Winter of 1963-64, before the first Central Vietnam casualty, Cape Girardeau became the battleground in a very different kind of war. For years the town’s leafless trees had frequently worn a weekend finery of white streamers left by roving bands of anonymous underclassmen not yet of driving age (and, therefore, at the two-foot end of the dating pool.)

That Fall a particularly active group of Freshmen that included Brad Leyhe was well known to have perpetrated a goodly number of raids, sometimes calling on as many as four houses in an evening.

[Editor’s note: I cannot verify any of the information my anonymous source has provided, so, please, Brad, don’t come looking for ME.]

Upperclassmen provided wheels

Such cavalry-like tactics were possible because of the relationship between carless underclassmen and occasionally dateless upperclassmen who, with nothing better to do, often honored such behavior by transporting the miscreants around town – for gas money, of course. This tradition, stretching back to the advent of the auto, helped bind Centralites into a more cohesive community.

Such cavalry-like tactics were possible because of the relationship between carless underclassmen and occasionally dateless upperclassmen who, with nothing better to do, often honored such behavior by transporting the miscreants around town – for gas money, of course. This tradition, stretching back to the advent of the auto, helped bind Centralites into a more cohesive community.

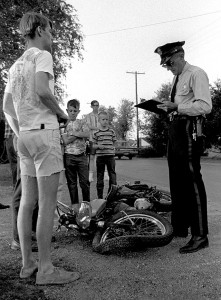

[Editor’s note: I am reasonably sure this vehicle was NOT involved in these escapades, but I’ve been looking for an excuse to use the photo for a long time.]

House left unguarded

By Thanksgiving 1963 the Leyhe band had developed quite a reputation as well as a number of revenge-seekers. During the week preceding, spies had learned that the Leyhes were leaving for a long weekend, their house on the back side of Capaha Park unguarded.

By Thanksgiving 1963 the Leyhe band had developed quite a reputation as well as a number of revenge-seekers. During the week preceding, spies had learned that the Leyhes were leaving for a long weekend, their house on the back side of Capaha Park unguarded.

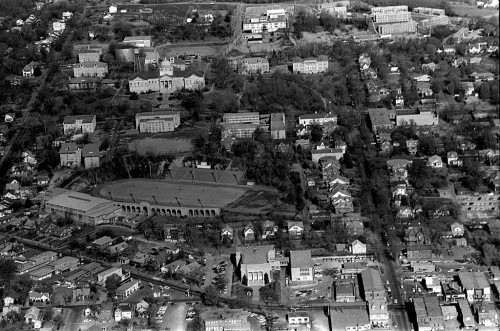

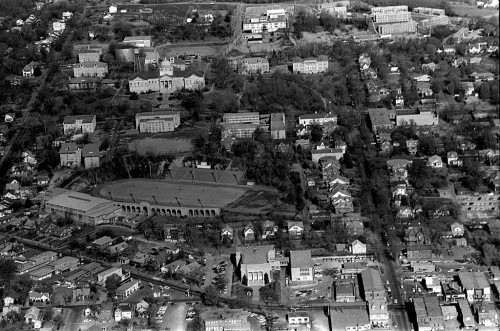

[Editor’s note: I have no idea where the Leyhes home is located, but this is a shot that shows Capaha Park in 1964.]

Black Friday evening an aggressive assault was launched leaving in its wake the effects of nearly two dozen toilet paper rolls and paraffin, not soap, covered screens (The difference being that while the latter washed out, the former had to be steamed off.) A second group mounted a follow-up mission Saturday night adding 20 or so additional rolls to those already in place. Worse, a fine rain fell early Sunday, plastering the paper to the bark and weakening the tensile strength of the streamers making them impossible to pull down. The family returned to a catastrophe of historic proportions, the remnants of which were to be seen for weeks afterward.

Central’s halls abuzz

Monday, Central’s halls were abuzz, as seemingly everyone had witnessed what the weekend had wrought. While opinions differed on the appropriateness of the response (hits to that time averaged 10 rolls), most recognized it as a harbinger of the significant escalation in the tenor of tee-peeing to come.

True, there had been the attempted Dearmont Quadrangle bombing a year or so earlier, but those were SEMO students with a plane. Not only did they miss the target, the outcome was a almost unrecognizable to a TP traditionalist. And, they got caught. While SEMO was to play a major part in the events of the next twelve months, it was the Thanksgiving weekend raid that sparked the most vicious period of paper sabotage Cape had ever seen.

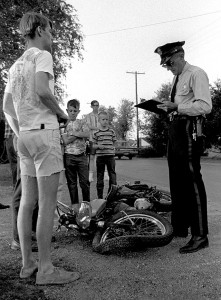

Officer Ravenstein frustrated

For the rest of that winter, officer Ravenstein and his colleagues were stretched thin as parent frustration mounted with the number, sophistication and severity of the incidents. Twenty then 30 rolls per house became the norm in the tit for tat of the escalating aggression. Syrup covered steps and burning brown bags were de rigor as the guerrillas’ numbers swelled to accomplish the forays in the limited time before police arrival. Whether the cops weren’t trying or the hamburger, an addition to every well-planned expedition, did indeed distract the dogs, no one’s parents got the late-night call to pick their kid up at the old police station that winter.

[Editor’s note: This photo of Officer Ravenstein has nothing to do with the story, but I wanted to run it anyway.]

As the months progressed, money became a key issue. Rolling was not an inexpensive weekend outing. At the time the minimum wage was about $1.30 per hour. A gallon of gas was less than 20 cents. A Wimpy burger and a cherry vanilla 7-Up cost a dime. When most late-night visits to Cape Rock were preceded with a stop at a favored drive-in (Wimpy’s, Pfisters or A&W) at a cost of less than a dollar, the $3 for materials (30 rolls at $.10 per roll) plus gas for the driver meant the Freshmen were paying more and getting less. Add to that the additional weaponry of syrup and soap and it was indeed a costly expedition. Things got so that it was impossible to find toilet paper in any public restroom, and many WWII veterans-turned-fathers were demanding to know who was wasting all of the bun wad at home.

Secret stash behind Houck Field

As allowances neared the breaking point, it became known that one gang had amassed a 100+ roll cache of purloined paper from SEMO. This revelation struck dread in rival bands, knowing that, if true, a superpower was in the making. After a few days and not insignificant bribes, the location of the secret warehouse was revealed to be the old seismograph building in the Home of the Birds. On a wet Saturday in early Spring rivals relocated the arms to an equally obscure site behind Houck Field.

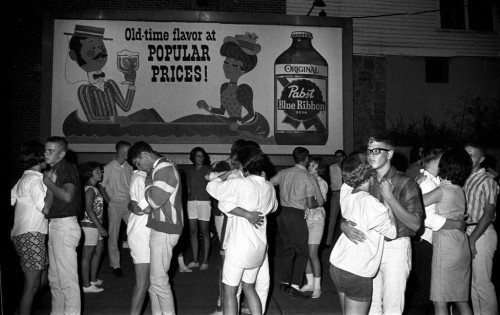

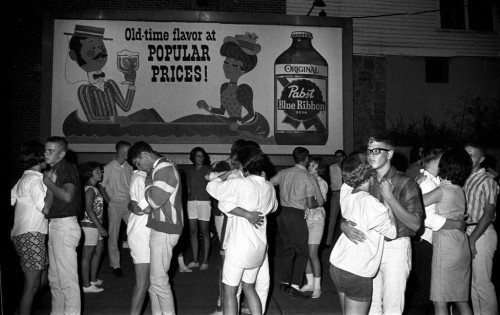

Late Spring brought the end of the papering season, the new leaves blocking and hiding streamers. A truce of sorts ensued as the off-campus focus shifted to the soon to be opened Teen Age Club at its second floor lodgings down from the Courthouse. Nevertheless, preparations for the anticipated renewal of hostilities when the leaves disappeared proceeded apace. Many were the raids on unguarded SEMO store rooms containing the treasured 100-count cartons of industrial strength toilet paper.

Resident Assistants would give chase

Occasionally some overzealous Towers RA would give chase, but these short-time visitors were no match for townies who had spent their kindergarten years with Miss Gross and a not insignificant portion of their youth mastering campus shortcuts. At summer’s end the Houck arsenal contained over 2,000 rolls awaiting the call to arms. [Editor’s note: these fellows are also irrelevant to the story, but I needed a running picture.]

Occasionally some overzealous Towers RA would give chase, but these short-time visitors were no match for townies who had spent their kindergarten years with Miss Gross and a not insignificant portion of their youth mastering campus shortcuts. At summer’s end the Houck arsenal contained over 2,000 rolls awaiting the call to arms. [Editor’s note: these fellows are also irrelevant to the story, but I needed a running picture.]

In September 1964 something – or more accurately 375 somethings – were missing at Central. Gone were the Freshmen, retained at the new Junior High, leaving the now Sophomores of the Class of ’67 again at the bottom of the high school heap. But, things were not as bleak as they might have been for the underclassmen.

Teen Age Club a success

Over the summer the Teen Age Club had exceeded everyone’s expectations, wearing out its original Themis Street digs, forcing a move to location number 2 (of at least 4) to the small industrial park behind Central. Not since the Mary Ann [roller rink] had parents of teenagers a place that would stand nominally in loco parenti. TAC offered a cheap, acceptable option to the risks of injury and capture by angry fathers and Cape police.

Over the summer the Teen Age Club had exceeded everyone’s expectations, wearing out its original Themis Street digs, forcing a move to location number 2 (of at least 4) to the small industrial park behind Central. Not since the Mary Ann [roller rink] had parents of teenagers a place that would stand nominally in loco parenti. TAC offered a cheap, acceptable option to the risks of injury and capture by angry fathers and Cape police.

[Editor’s note: TAC was so popular that the building inspector was afraid the gyrating teens were going to cause the floor to collapse, so the dance was moved to a bank parking lot.]

Still, in late October when fires flared in the gutters and Cape was awash with the aroma of burning leaves, white streamers reappeared with a vengeance. But, early in the renewed hostilities campaigners received their first major blow.

Father tipped off

Ironically, it came not from the police or irate targets, but the father of one of the more daring organizers. [Editor’s note: that’s actually my dad relaxing in his recliner in our basement.]

Ironically, it came not from the police or irate targets, but the father of one of the more daring organizers. [Editor’s note: that’s actually my dad relaxing in his recliner in our basement.]

Acting on a warning from a double agent, the Stahly Brothers, waiting in ambush, inadvertently tipped him off. What followed is best unrecorded. However, with the son laid low, many of the feuds that had fueled the fighting faded. For the few remaining fanatics, a new enemy had to be conjured, and what better than the students at Notre Dame.

Notre Dame the new target

Despite their close proximity, traditionally there had been little interaction between the two student bodies. Just how much of this related to past religious prejudice is beyond the scope.

Things were changing. TAC offered a neutral ground for prolonged contact beyond that of basketball field house or a cross-car conversation at a drive-ins. Familiarity may breed contempt, but first it brings recognition and romance, both still a ways away as the cold winds of November swirled into Cape.

Planning had already begun for a massive raid on Notre Dame itself. The school was scouted, targets plotted, escape routes planned and for weekend traffic patterns/police patrols studied. No detail was omitted.

Planning had already begun for a massive raid on Notre Dame itself. The school was scouted, targets plotted, escape routes planned and for weekend traffic patterns/police patrols studied. No detail was omitted.

Given ND’s relative isolation, it was estimated that there would be about an hour of uninterrupted on-site time. Experience indicated that in 60 minutes a well-practiced team of 6 could put 400 rolls on target. Extra laundry bags, the secret to moving TP invisibly, were acquired and the date, coinciding with a covering dance at Central, chosen.

At the gym that evening two team members bowed out, but an out-of-town guest joined, making the strike force five. The decision was made to proceed.

The plan went into the toilet

It was a dark night, and things did not go as planned. First there was difficulty in locating the bags pre-positioned that afternoon. Then it was discovered that full roll thrown to the school roof tended to keep going, pulling the streamer up after it. The adjustment required the trees close to the convent be covered first (increasing the risk of discovery), and the then the almost spent rolls be taken up to the school building. Shrubs were wrapped and confetti sown into the lawn. Things were proceeding, but well behind schedule, when the lookout radioed over the walkie-talkie, “Cops.”

The team escaped without difficulty using the pre-determined routes. Within half an hour, all reported to the rally point. There it was discovered that some of the laundry bags were left behind. And, on those bags were identification markings.

It was Midnight when the bag boy slowly crept through the cemetery bound for the temporary ammo depot. It had been an hour since the alarm, and the police had never before stayed longer than twenty minutes. So it was nearly wet pants when one jumped from behind a gravestone demanding a reason for the trespass.

Payne Muir wasn’t happy

The fraternity initiation story sounded good until the now perp entered the squad wagon. There sat Central coach Payne Muir, a nearby resident, fuming about his slit tires. It was he who had called in the alarm, and it was that on which the investigation had focused until the Sisters notified the officers of the school’s desecration. And, there in the back-end were the laundry bags.

The fraternity initiation story sounded good until the now perp entered the squad wagon. There sat Central coach Payne Muir, a nearby resident, fuming about his slit tires. It was he who had called in the alarm, and it was that on which the investigation had focused until the Sisters notified the officers of the school’s desecration. And, there in the back-end were the laundry bags.

The subsequent juvenile hearing was unremarkable until one of the defendants, when asked by the judge, “Why?” responded, “There’s a certain beauty to it.” To which the judge retorted, “Judge Statler (the circuit court judge with ND connections) may not think so. The next time this happens it goes before him (meaning trial as an adult).”

Thus ended the year of living dangerously. Tee-Peeing on a large scale became almost a lost art as Judge Statler’s dictum reverberated around town. As for the devastation at Notre Dame, no one ever saw it all. What the Sisters didn’t clean-up that evening, the usual cast of Notre Dame detentioners did at 7:30 the following morning. Not even Kenny Steinhoff got a photo. [Editor’s note: True, unfortunately.]

Post script – In 1989 a crew demolishing the old picnic pavilion behind Houck’s Rocks found nearly 700 rolls of old toilet paper stashed in the long locked cabinets. They were disposed of still in their wrappers.

I tried to find out when Cape added radar to its arsenal of speed-fighting tools, but came up empty. I DID see a story in The Missourian Aug. 29, 1957, saying that Missouri had set an upper speed limit for the first time. It and Kansas had the highest speed limits in the country – 70 mph.

I tried to find out when Cape added radar to its arsenal of speed-fighting tools, but came up empty. I DID see a story in The Missourian Aug. 29, 1957, saying that Missouri had set an upper speed limit for the first time. It and Kansas had the highest speed limits in the country – 70 mph. This picture was taken in front of the Arena Building. It, like the shot above, were stock-trade-hack newspaper photos. Obviously, I was sent out to shoot a bunch of people pretending to interact.

This picture was taken in front of the Arena Building. It, like the shot above, were stock-trade-hack newspaper photos. Obviously, I was sent out to shoot a bunch of people pretending to interact.